I’m very much an armchair historian when it comes to some of this planet’s horrifically destructive conflicts over the years.

I could sit and talk about trench warfare in the First World War for hours. I could sit and talk to somebody about Wehrmacht movements across Europe for hours. I could sit and talk about the rise and use of air cavalry in the Vietnam War for hours.

However, something I’m a little less knowledgeable about is the Great Emu War that occurred late in 1932 in Australia.

So, it’s time for us to all do a little learning together…

Emus are Australia’s National Bird.

Before I go into any of the backgrounds to this… “conflict”, I just want to talk about the concept of a National Bird.

The idea of a National Bird is one of national pride and symbolism.

From the start of time, people have always responded to symbolism when linked with nationalism – and we even see it nowadays on a smaller level with football mascots or office pets.

Let’s look at India’s National Bird, for example, the Indian Peafowl.

The Indian Peafowl is a beautiful creature whose vibrant plumage represents the beauty of India. As such, it is a protected species in India.

The American Bald Eagle symbolizes patriotism, bravery, and freedom to all Americans, and – like India’s coveted Peafowl – is a protected species in its country.

The National Bird of Australia is the Emu, and it is considered far and wide to be a pest that is tasty – and it is most certainly not protected, as we’re all about to find out…

A little bit of backstory…

Following World War I, large numbers of returning Australian soldiers (as well as British veterans) were given swathes of land for farming by the Australian government.

When the Great Depression hit in 1929, these farmers were encouraged to up their wheat production on the back of promises by the Australian government that these would be subsidized.

However, these promises failed to come to fruition leaving the farmers even more out of pocket than before.

So, what could possibly make this situation any worse?

As it so happened, 20,000 emus had just finished their breeding season on the coast and were now making their regular migration inland only to find the once-barren outback was now fertile farmland full of tasty, tasty crops.

The emus smashed through the wooden fences, devouring the farmers’ crops, and leaving gaps in the fences big enough for rabbits to come in and finish off anything the emus had missed.

This caused outrage with the farmers who, in their desperation and despair, sought help from the government.

Now you might think the logical government department to appeal to would be the Ministry of Agriculture.

However, these farmers were mostly military veterans, and as such, they sought help from the Ministry they trusted the most: The Ministry of Defense.

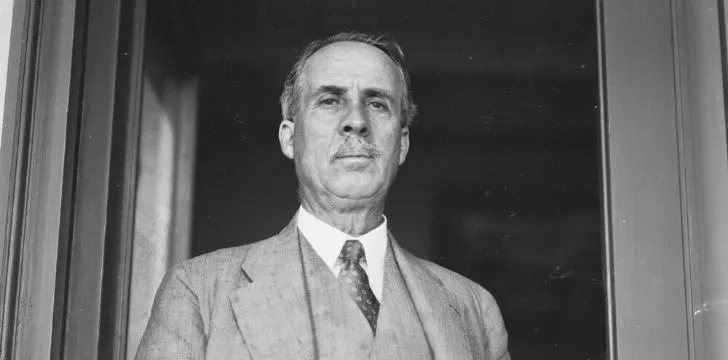

Sir George Pearce and the Declaration of “War”.

Australia’s Minister of Defense was Sir George Pearce, and he was heavily respected by the Australian veteran farmers.

When the soldiers argued to Pearce that military machine guns would be the best way of culling the emus, Pearce agreed happily.

The rules of engagement were set for the upcoming war: all “soldiering” and handling of weapons would be done by Australian troops and financed by the Australian farmers, who would provide the soldiers with accommodation and food.

Pearce also supported the engagement with the hopes that the emus would provide some good target practice for the Australian machine gunners.

This war was supported by the Australian parliament as they believed it would be a good way of showing that it supported its struggling farmers.

To that end, a propaganda film crew from Fox Movietone were assigned to the soldiers to document their (and the government’s) triumph for the public to see.

With the go-ahead given by parliament, a crack Expendables-esque team was created to carry out the war’s combat operations.

The brave soldiers of humanity!

With military involvement set to kick in at the start of October 1932, three highly-trained troops of the Seventh Heavy Battery of the Royal Australian Artillery were deployed.

Commanding them was Major G. P. W. Meredith – a decorated World War I veteran with a great combat record.

Under him were Sergeant S. McMurray and Gunner J. O’Hallora – both armed with a Lewis machine gun and 10,000 rounds of ammunition.

After a month-long delay due to some rather torrential downpour, the operation final commenced on November 2, 1932 – a day that would live on in wartime infamy.

The Opening Battle

With the players all in place, the stage was set for a spectacle. The men traveled to Campion, following rumors that there was a group of 50 emus around there.

However, the emus were out of machine gun range so local settlers and farmers herded them into an ambush… or at least they tried to.

The thing about emus is they’re very hard to hit targets. Now I know what you’re thinking; “but they’re like 6.5 feet tall, how could they be hard to shoot?”

Well be that as it may, emus are fast. They can run at speeds over 30 miles per hour (48 km/h) – a fact not lost on the emu high command.

So, at the Battle of Campion, when the locals tried herding the emus and the machine gunners opened fire on them, they just ran away and split up into smaller groups – making them virtually impossible for the soldiers to hit.

Despite hitting “a number” of birds, and then later in the day “perhaps a dozen”, the emus had mostly escaped unscathed.

Emus 1 – 0 Australia.

The Conflict Escalates…

On November 4th, Major Meredith and his men moved towards a dam where more than 1,000 emus had been spotted.

This time, they utilized their best stealth sneaking skills to get up close to the emus before opening fire.

As the machine gunners let their barrage loose it turned out the stealthy approach had paid off.

Until one of the machine guns jammed after killing 12 birds…

The remainder of the birds scattered – and Major Meredith had come to learn that the emus could easily survive a single bullet wound and run away before receiving another.

No more emus were spotted or attacked on November 4th.

Emus 2 – 0 Australia.

Understanding the enemy and a change of tactics…

The conflict continued as Major Meredith and his men moved south, hot on the heels of some supposedly “fairly tame” emus.

However, Major Meredith and his men had very limited success.

It was around the fourth day of the campaign that army observes seemed to note that “each pack has its own leader now” a bird that “keeps watch while his mates carry out their work of destruction and warns them of our approach”.

So, with the observation of a military command structure, and full-well knowing the emus’ strength was their speed, Major Meredith ordered one of his machine guns to be fitted to a truck.

With one of the machine gunners positioned on the truck-mounted gun, he was driven at speed into the crowd of emus.

However, the fact that the terrain was so bumpy and rocky meant that he didn’t even fire one shot. Talk about losing yourself…

Emus 3 – 0 Australia.

Ending the conflict.

By the end of November 8th, only six days after the first battle, the operation was reviewed by the Australian House of Representatives.

With negative media coverage courtesy of the film crew attached to the troops and reports that as few as 50 emus had died for the 2,500 rounds of ammunition fired, Pearce was forced to withdraw from the military.

After the withdrawal, Major Meredith was quoted as saying: “If we had a military division with the bullet-carrying capacity of these birds it would face any army in the world”.

The war was over… or so it seemed.

The return of war!

After the war was officially called off, the farmers were none too pleased.

To make matters worse, hot weather and drought had bought the remaining emus further inland.

With roughly 19,700 – 19,950 emus left (depending on your sources), Pearce announced the war was back on.

With Major Meredith and his troops back on the case, the military started to actually see some mild successes.

By December 2nd, the soldiers had reported they were killing approximately 100 emus a week.

But on December 10th, Meredith was recalled and, having expended 9,860 rounds on a reported 986 kills (that’s 10 rounds per confirmed kill), and claiming that a further 2,500 emus had died of wounds received in battle, the operation was deemed a success.

The war’s aftermath.

You don’t have to be a mathmagician to know the numbers don’t add up.

With – at most – 4,000 emus killed, there were still up to 16,000 emus running around still causing havoc for the farmers.

Whilst the government had initiated a bounty system on emus that saw some success, all in all, the emus had still been the successors of the war.

So how did the Australian farmers – seemingly abandoned by their government and their people – overcome this dark period in Australian history?

Well, they just started using metal chain-link fences instead of wooden fences.

Nope, seriously, that’s it.

That’s what ended the Great Australian Emu War of 1932.